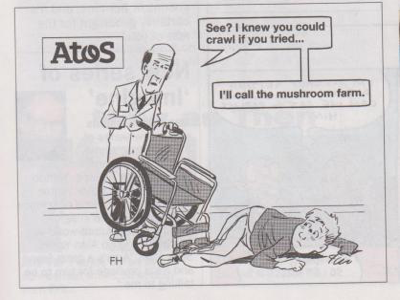

I co-run a support group for people going through Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) and Personal Independent Payment assessments and appeals. I have heard many people's harrowing experiences of these assessments, I have written about them, and I've written critically about the assessment process itself. However, it isn't until you experience one of these assessments for yourself that you may fully appreciate just how utterly distressing, surreal, degrading and dehumanising the process actually is.

I had my first ever Personal Independence Payment (PIP) assessment today. I have systemic lupus and pulmonary fibrosis, among other problems, all of which affect my mobility and capacity to live independently, day-to-day. My consultant is a rheumatologist and more recently, I have been seeing a pulmonary consultant. Other specialists I sometimes need to see are a neurologists, opthalmologists, physiotherapists and haemotologists.

After a bout of pneumonia and sepsis earlier this year, which almost cost me my life, a follow-up scan found further lung problems, which have probably been ongoing for some time. Fibrosis can happen as a result of connective tissue illnesses like lupus, scleroderma or rheumatoid arthritis. It can also happen to people whose conditions have been treated with a chemotherapy called methotrexate - which I was given from 2012 onwards. My mother, who had rheumatoid arthritis, died suddenly of pulmonary fibrosis in 2009. The coroner said it was a complication of her illness, not because of a treatment.

The interview part of the assessment seemed okay. I provided further evidence regarding my recent assessment that was undertaken by my local council's Occupational Therapy Service, which led to the prescription of aids and appliances in my home. The assessment report was quite clear about my basic medical conditions and day-to-day mobility limitations. I was asked about medication. I explained that following my second appointment with my new rheumatologist, I was prescribed some new medications, including one for secondary Raynaud's syndrome, which has arisen because of my having lupus, as a complication.

A recent thermal imaging and microvascular study shows that this condition has got worse over time, and so my rheumatologist prescribed a treatment called Amlodipine. It concerned me that the Health Care Professional looked confused and skeptical when she asked for a list of my medication, and she said that this is a treatment for high blood pressure, she seemed to disbelieve what I had told her. I explained that I don't have high blood pressure, and that calcium channel blockers such as Amlodipine are used for more than one condition, such as certain types of angina - which I also don't have - and secondary Raynaud's syndrome, which I do have.

I was asked about the impact of my illnesses on my day-to-day living. At one point I explained that I find preparing and chopping food difficult because of the tendonitis in both wrists. I have been diagnosed with De Quervian's Tenosynovitis, which makes putting any weight or strain on my wrists very painful.

I was also concerned that I was then asked if I have had my wrists splinted. This shows a lack of understanding about my condition. I have had splints but it did not make any difference to my wrists. I was diagnosed with De Quervain's syndrome by my rheumatologist and a physiotherapist in 2011, but had the problem for considerably longer. As my physiotherapist pointed out, my wrists are not injured or strained through strain and overuse and so won't get better with rest or splinting. This is because they are damaged by a chronic systemic inflammatory disease process that is ongoing, and he told me it is medication rather splinting that is needed to try to manage the inflammation.

Splinting my wrists is akin to putting a plaster cast on a knee affected by rheumatoid arthritis, or a plaster on cancer. It won't help at all. That the HCP didn't seem to understand the difference between the chronic inflammatory symptoms of connective tissue disease and curable strain and injury related conditions bothered me.

After discussion of my conditions and how my illnesses impact on upon my day-to-day living, I was asked to do some tasks during an examination, which have left me in a huge amount of pain. I also felt stripped of dignity, because I struggled to manage the exercises and felt very anxious and distressed. I was shocked at some of the tasks I was asked to do, and also shocked at the fact I couldn't actually undertake a number of these tasks. My shock turned to anger later, as I had to leave in significantly more pain that I had arrived with at the start of the appointment. I was also asked to do each of the unfamiliar tasks and exercises in quick succession, which made assessing any likely pain and damage difficult before trying to do them.

It is also a traumatic experience to suddenly discover that your illness has insidiously robbed you of a degree of mobility that you previously assumed you had. It's always a shock.

I have, among other problems, very painful inflammatory arthritis and tendonitis in my knees, hips, spine, Achilles' tendons and ankles. Because the inflammation and damage is bilateral and symmetrical - affecting both knees, both hips, both ankles and both Achilles' tendons equally, and across my lower spine - it leaves me unable to compensate for pain, stiffness and weakness by shifting my weight and balance onto another limb, as that is also weak, stiff and painful. It leaves me unsteady. I often use a stick to stop me falling over, but as an aid for walking, it's pretty useless generally, because my shoulders, elbows and wrists also won't take any of my weight.

The inflammation process causes marked stiffness as well as severe pain, and so restricts my mobility. I was asked to "squat down". I told the assessor that I couldn't do that. It would have certainly caused me severe pain and possibly an injury. As I can't support weight on my shoulders and wrists - I also have osteoporosis in my wrists and hands - had I tried and fallen backwards, I may have easily ended up with a fractured bone. I was horrified at being asked to do that. I struggled to equate the "health care professional" with what I had been asked to do, and felt confused and shocked that she had asked me to do something that may have been harmful.

I also felt that the HCP may have misconstrued my comments that I couldn't undertake this task as an unwillingness to cooperate, as she looked unhappy about it. She did ask why, and I explained. I felt that trying some of the other tasks she set, which looked to be less dangerous, would at least demonstrate that I wasn't being uncooperative, and most looked like they wouldn't inflict any damage at first glance, when she demonstrated them.

However, other exercises I tried to do resulted in my neck locking and severe pain when I was told to turn my head to look over my shoulder - and couldn't. I have neck problems through longstanding inflammation there and an upper spine injury involving a displaced vertebrae, which is sometimes very painful. In addition, the problems in my shoulders also contributed significantly to the level of pain when I turned my neck, and my neck clicked painfully at the base of my skull.

I was asked to put my hands and wrists in positions that looked impossible to me - I felt that only contortionists and very double jointed people could probably manage it. I tried, though. I was asked to line the backs of my wrists up with my hands flat, which I couldn't do, and it hurt me a lot to try this.

This is called Phalen's Manoeuvre. I was asked to do what is actually a provocative diagnostic test for carpal tunnel syndrome - which entails compression of the median nerve. The test provokes the symptoms of carpal tunnel problems, in the same way that the painful Finkelstein test provokes symptoms of severe pain in people with De Quervain's. I have never been diagnosed with carpal tunnel problems, but I do have more than one diagnosis of bilateral De Quervian's Tenosynovitis, as stated previously.

I tried to do this manoeuvre, even though it isn't applicable to my condition (though I didn't know that at the time, I have since researched the test, as I wanted to know why I couldn't perform the task). I couldn't even get close to managing it, it hurt my shoulders a lot when I tried to align my arms at right angles with my wrists, and I couldn't drop my wrists fully due to an incredible pain and stiffness that I had not expected. The backs of my wrists simply painfully refused to meet.

I do struggle with pain when putting any weight on my wrists, but didn't realise how much they had stiffened up, restricting their movement. Not being able to perform this movement doesn't mean I actually have carpal tunnel syndrome. Nonetheless, I feel that given my previous concrete diagnosis, I was put through this painful and traumatic series of medical tests for no good reason.

This is the problem with a short assessment of complex conditions. Many of my problems and diagnoses go back years, and only some of them are summarised neatly on my consultant's report. My relationship with my new rheumatologist started in April, my old one moved in 2015. My new rheumatologist decided to "challenge" the previous diagnoses of two former rheumatologists. Her report to my GP was woefully inaccurate because she had not read my notes or listened to what I told her.

Long story short, she re-diagnosed me with with fibromyalgia, she didn't read my notes, she sent me for tests and scans I had already had previously, whilst suspending my treatment pending results. The scans and tests took months. That resulting in a serious lupus flare, which culminated in a bout of pneumonia and sepsis. During the time I was in hospital, I was re-diagnosed with lupus following abnormal test results, which was thought to be the key reason why I had got so ill - unfortunately, lupus leaves me very susceptible to serious infections like pneumonia, kidney infections and sepsis. I now have a new rheumatologist who says I definitely have lupus.

Atos say they won't cary out 'diagnostic tests' but they did.

In the appointment letter from Atos, it says: "The Health Professional will talk to you about how your health condition affects your daily life". Much of this was covered with the council's initial care plan report, but I did discuss my health issues and barriers to independence at length during the assessment.

The letter from Atos then says: "This will not be a full physical examination or an attempt to diagnose your symptoms."

My neck and shoulders are stiff, painful and I currently have limited mobility in them, yet I was asked to put my hands behind my head, raise my arms and so on. Loud joint cracking, popping, creaking and gasps of pain and my screwed up face didn't stop the demands of the impossible. I was actually sweating and trembling with the effort and pain, and still she did not stop. I felt I couldn't say no, as I would have seemed somehow unreasonable. I kept thinking that if I tried, gently, I was at least showing willing, and that would be okay, but unfortunately I wasn't.

It's difficult to equate these artificial manoeuvres with day-to-day activities, and therefore it is also difficult recognise the impact it would have on my mobility limits before I tried them and to gauge how much a movement in isolation is going to hurt.

Immediately following the examination/tests, my left calf has inexplicably swollen to twice its normal size, I could feel the uncomfortable tightness in it, and the swelling was visible through my jeans, whilst still with the assessor, and I commented on it.

My pain level has significantly increased everywhere. I had no groin or neck or elbow pain when I arrived until I was asked to do activities that were beyond my capability and that caused me a good deal of pain. I felt undignified trying to do those tasks, shocked at the pain, and sometimes, at how limited my movements have become. It was an extremely distressing and dehumanising experience. I was also shocked at how the effort made me tremble and sweat, and at how my clear distress was completely ignored

Of course I am going to make a formal complaint about this. It shouldn't cause people so much pain and distress to be assessed for support. And any examination part of the assessment ought to take your medical conditions and descriptions of mobility constraints fully into consideration without a grueling and painful examination regime.

It is worth bearing in mind that in addition to my own account, medical evidence from my rheumatologist was submitted in advance, and a report of recent assessments by a council occupational therapist who prescribed aids and adaptations, which clearly outlined my mobility difficulties, following two assessments, was also submitted. This was a report written by a qualified professional and was based on her own examination of my level of functionality and mobility while I tried to perform directed tasks in my home, such as climbing stairs, preparing food and using a bath board in my bathroom.

The fundamental difference between the assessments is that the one for my care plan allowed me to undertake tasks at my own pace, with dignity, and the Atos assessment did not. The former also felt like it was a genuine assessment of my needs, with support being the aim, whereas the latter felt like some sort of skeptic's test to see if a way could be found to claim my account and those of my doctor were somehow incorrect. The Atos assessment was so horrifying because it felt like it was about reluctantly providing support for maintaining my independence as a last resort only.

According to the government's PIP handbook, for a descriptor to apply to a claimant they must be able to reliably complete an activity as described in the descriptor. Reliably means whether they can do so:

safely – in a manner unlikely to cause harm to themselves or to another person, either during or after completion of the activity.

The descriptors at no point demand that a person completes the Phalen manoeuvre or squats. The brief and painful completion of raising your hands above your head does not demonstrate either a fluctuating ability to do so, or your ability to hold your arms up long enough to, say, wash your hair and rinse it, even on a good day. Nor does it account for profound fatigue, coordination difficulty and breathlessness that often impact on any performance of that task. I did this point out, and the fact that they activities had left me in a lot of pain.

It's now the day after my PIP assessment. I am still in a lot of pain with my joints and tendons. I feel ill, anxious, depressed and I am still shocked and angry. I can't even manage to wash today. I have also developed pain on the left side of my chest, which feels rather like pleuritis. I feel really unwell, profoundly tired and haven't felt this bad since my bout of pneumonia.

No-one should be made to feel worse because of an assessment for support. The activities I was asked to do should have been stopped when it became clear I was struggling. I stated I was in pain, I was visibly sweating, trembling and clearly in a lot of pain with the effort, and as a "health professional", the assessor should have halted that examination. I am concerned that unintended harm may be caused by assessors because they do not have sufficient information or understanding about patients’ conditions.

My condition, for example, has left a trail of individual symptom diagnoses and medical data that goes back many years. With such a complex array of joint and tendon problems, I felt that there was absolutely no consideration of the impact that, say, hand and wrist manoeuvre may have on a person's damaged shoulders, or how a neck movement may impact on an upper spine injury and inflammatory shoulder problems, as well as the neck.

Given the assessment report I submitted and medical evidence, in addition to my own account, I feel that such a painful physical examination ought to be restricted to cases of absolute necessity. I don't believe those movements I was asked to do demonstrate limitations on my day-to-day independence, and how I manage (or don't) to cope with domestic tasks and general mobility.

The fact I couldn't do some of them was both traumatising and humiliating, as well as very painful. The shame of being there to explain to a stranger about your illnesses, the intimate details of your life, your vulnerabilites and why you need help, is difficult enough, without the added distress of being assessed by someone who doesn't understand your conditions and does not care that what they ask you to do may be both painful and damaging.

Kitty S Jones | June 28, 2017 at 7:35 pm

Thursday, 29 June 2017